“Ballpoint King” Thien Long: I Succeeded Because I Dared to Trust People

03 Sep 2025

— For nearly 45 years, Thien Long ballpoint pens have become familiar to generations of Vietnamese and are now present in more than 70 countries and territories. That journey began from a very small workshop you started in the early years after national reunification. What brought you to a product that ended up changing your entire life?

— I’m the eldest of ten children, living with my parents and grandmother. After reunification, I was only 17. Seeing how hard my parents worked to feed 13 people and still came up short, I knew I had to do something to help, so I decided to go out and hustle.

Back then, not only stationery but even daily necessities were scarce. Every time I passed the school gates, I saw guys refilling ink and repairing pens with many customers gathered around. I realized demand for pens was huge. Looking deeper, I learned that there were already a few small workshops in Ho Chi Minh City making pens, which meant there was a market—but no one was doing it properly. I asked myself: Why don’t I try selling pens?

I put together my small savings, grabbed my rickety bicycle, and that became my capital. As the eldest son carrying family responsibility with very little money, I decided to trade pens. I wasn’t thinking big—just trying to make a living. I went to small workshops, picked up a few dozen pens, then resold them to newsstands and bookstores.

The work yielded results at first, and I gradually built up capital. In 1981—by then I had two gold taels—I decided to switch to producing pens myself.

— With such limited capital and no manufacturing experience, why take that leap?

— I didn’t stop to think whether it was risky; I only knew it was what I had to do to earn money to support 13 family members.

At the beginning, it was just a family operation—siblings and parents—with very few machines. The “factory” was mainly an assembly because there was a local Chinese community that had been developing cottage industries before 1975, already producing plastic tubes for pen barrels, refills, tips, etc.

(Photo: Mr. Co Gia Tho hand-assembling pens in the early startup years. Courtesy of the interviewee.)

At that time, the wholesale market was centered at the Binh Tay and Phung Hung markets. I was new, without a name, and couldn’t break in. To sell goods, I had to “sell on consignment”—leave products first and only collect money after they sold. With such limited capital, I couldn’t afford that. I only had enough to buy materials for three days of production. Once we finished, I’d pedal my old bike across the city from morning to evening, wholesaling to newsstands and bookshops. Only by the fourth day, after selling out, did I have cash to buy the next batch of materials. We rolled forward like that, batch by batch.

By 1982, I finally began entering the wholesale market. A year later, I got married. My wife had an entrepreneurial streak early on—she used to wholesale soap at the markets, which is how we met. With her help in delivering pens and collecting payments, I had more time to focus on production, R&D, quality, and expanding the workshop.

— In the late 1990s, Thien Long was one of the first companies to set up in Tan Tao Industrial Park with encouragement and support from the government. What advantages did that decision bring?

— That too was a matter of timing. My principle has always been: wherever we operate, that place should develop. Even when I just ran a small shop, I was active in community work and served as Vice Chair of the local charity association in Ward 6, District 6, in the late 1980s. Our production practices were recognized by local authorities, so I was often invited to meetings about reform and small-industry development.

When HCMC rolled out a policy to provide interest-free loans to companies that committed to hiring more workers, I applied for a VND 200 million loan at 0% interest and hired 200 workers. That became a solid springboard for Thien Long.

Around 1995, the city initiated and encouraged businesses to move into Tan Tao Industrial Park to create flexible, standardized production sites that were easier to manage and better for the environment. I saw this as the right direction and signed up. In 1996, Thien Long bought 1.5 hectares in Tan Tao and built a factory. At the same time, the city launched another policy working with banks to finance 70% of plant construction for companies in Tan Tao, so we only needed to contribute 30%. It was an excellent policy—a win for all three parties: the state could plan industrial production, businesses could invest properly, and banks had reputable clients.

By late 1999 and early 2000, we officially moved production to Tan Tao. Previously, our old site was just over 2,000 m² and crowded with machines. The cramped space prevented us from increasing productivity or specialization. Once inside the industrial park, everything changed. We organized more professionally, established R&D, quality management, wastewater treatment, and more. From a small workshop, Thien Long gradually became a professional enterprise.

(Photo: Aerial view of Thien Long’s factory in Tan Tao Industrial Park, HCMC. Source: TLG)

— Fifty years since reunification, HCMC has undergone many economic reforms. What have those changes given—or taken—from Thien Long?

— Thien Long is now 44 years old, having witnessed and participated in many policy shifts—from very difficult early days to today’s leading regional economy. We started as a household business, then an individual enterprise. Later, the government called on all small producers to merge into a consortium, similar to a cooperative. At that time, there were two pen manufacturers in District 6, so we were grouped.

In principle, the model was sound—leveraging collective strength. But there were no clear laws yet on capital contributions or trademarks, so the consortium structure wasn’t fully formed. To formalize the model, we created product lines under a shared brand, but consumers were already familiar with each company’s individual brand, so jointly branded products weren’t well received. Moreover, grouping competitors into one consortium sapped each brand’s motivation. It was a “formal” merger without unity of purpose.

After some time, I petitioned to leave the consortium. Fortunately, the government recognized the issues, approved the request, and adjusted policies.

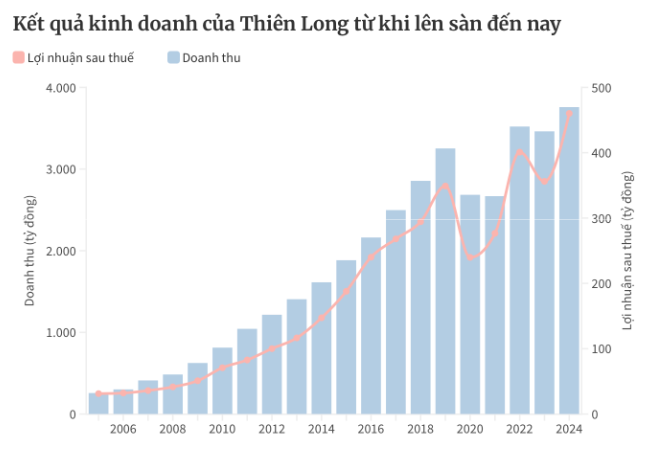

By 1995–1996, Thien Long became a limited liability company, later a public joint-stock company, and was listed on the stock exchange. We experienced many different economic regimes and learned a lot. I feel blessed to live in a country progressing every day—it motivates me to develop personally and to grow the business.

— After so many years, have you considered joint ventures with foreign partners to accelerate growth?

— As a listed company, Thien Long has engaged with and received capital from many foreign shareholders and funds. Before the pandemic, we welcomed a leading U.S. consumer and home-goods brand as a strategic shareholder with over 7% ownership. Our stance is cooperation without joint ventures—we won’t lose our Vietnamese brand identity. To date, that foreign shareholder group has partly exited and is no longer a major shareholder.

I believe we live in an open, borderless era; whether you’re acquired depends on your own policies. When taking investment, you should design win-win mechanisms to grow the market “pie” and create synergies in technology, markets, and more.

— Beyond COVID-19, what other “storms” did Thien Long face on its journey?

— In 2008, during the global financial crisis, we faced a truly tough test. Before that, we had bought two plots for expansion: one in Dong Van Industrial Park (Ha Nam) to add products like notebooks, pencils, and chalk; the other in Sonadezi Long Thanh (Dong Nai) to expand file-folder production and increase capacity for pens and stationery.

The Ha Nam project had a total investment of VND 200 billion—a huge sum. But bank interest rates at times reached 20–30% per year, so we had to shelve the new-product plans in Ha Nam and focus resources on the Long Thanh project. Aside from that episode, our 40-plus-year development has been relatively smooth.

Of course, every period brings its own challenges—that’s business. Whatever the approach, internal strength matters most. If a company’s core isn’t strong, even small problems are hard to overcome. From our earliest days, we focused on building management foundations: quality systems, workplace safety, production safety, and worker health. That’s why our products can be exported to demanding markets, including the U.S.

We’re strong in people and finances, which reinforces trust among customers and investors. With sound finances, we could stockpile raw materials during inflationary spikes and limit price increases, sparing consumers from the burden.

Even as competition intensifies with more foreign brands entering, we’re confident in our sales muscle. Our products cover all channels: traditional trade, modern retail, B2B, e-commerce, bookstores—and we’re preparing O2O (online-to-offline) models.

— Many companies with strong finances and internal strength diversify. What about Thien Long?

— We do pursue diversification. We began with pens and stationery and have expanded into art-related products.

We’re piloting student lifestyle items like water bottles and backpacks, and moving toward greener, safer products—for example, pens used in operating rooms. But our diversification stays within our industry; we have no plans to branch into unrelated fields.

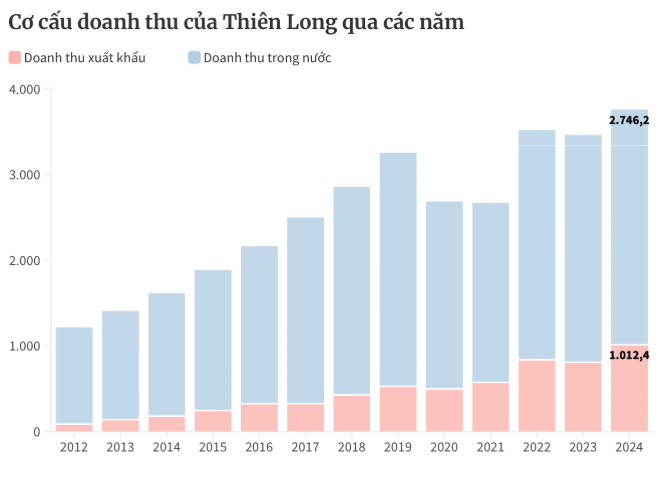

Beyond widening the product portfolio, we’re expanding regionally. In Southeast Asia, many pen and stationery players have been shrinking or moving into larger, more profitable sectors. Thien Long, however, started exporting early and has grown continuously for many years. According to Agency MRF, CAGR across Asia-Pacific is only 5–7%, yet Thien Long achieved 25% growth in 2024. Exports now contribute 20% of revenue. Over the past decade, overseas sales have seen multiple double-digit growth years, and in 2024, for the first time, we surpassed VND 1,000 billion abroad.

We aim to raise that share in the coming years through a glocalization strategy—leveraging domestic strengths (local) and adapting them for international markets (global). Our goal is to rank among the top five pen and stationery companies in Southeast Asia, which offers strategic geography and demographic, cultural, and economic similarities.

— You’ve spoken of a “4–6” business philosophy: keeping 4 parts for yourself and giving 6 parts to others. Can you elaborate?

— In life and in business, people often seek a 5–5 balance so no one gets more. I think happiness is what matters. I started from zero—life was very hard—but I was still cheerful. So getting even 1–2 parts already felt like happiness, let alone 4 parts. People must learn to accept; otherwise nothing is ever enough.

This isn’t just in business—I tend to yield a little when collaborating with friends or in meetings.

I remember in the 1980s, a friend in Long An asked me to partner in buying watermelons to sell in the city during Tet. Watermelons were seasonal then, not available year-round. I agreed to join. Since it wasn’t my field, I let my friend take the lead and asked for a smaller share of profits. Friendships aren’t just about gain; bonds and loyalty matter more.

This philosophy—and the desire to uplift our operating environment—led Thien Long to do CSR early on. I believe only when the surrounding environment thrives can we be truly happy. So we always focus on sharing, helping, and contributing to common development. While every person and company has limits, we concentrate our CSR on education, the foundation of national development. Beyond the 23-year-running “Exam Season Support” program, we also aid struggling teachers and organize children’s drawing contests.

— You once said, “Whatever you do, make sure you sleep well at night.” What does that reveal about your life and work?

— I like solidity and keep a measure of control. Before acting or responding, I think about whether the other party will be satisfied and if anything might trouble them. As a result, I’ve been blessed with steadfast friends, reliable partners, and loyal colleagues. Being straightforward and uncalculating helps me sleep soundly every night.

I apply the same in business. As a joint-stock company, I’m accountable to shareholders and must give them peace of mind through financial sustainability, transparent systems, and risk avoidance.

At the same time, I believe in living honestly—say what you think and do what you say. Sincerity matters most between people. With those I’m close to and respect, I’m even more candid.

To live honestly, I consider myself an open book. I’m willing to listen to criticism from anyone—even employees—about where I’m wrong or lacking. I’m not afraid to share my shortcomings to receive guidance from experts.

— Over 40 years, Thien Long has repeatedly renewed itself and avoided “getting old.” What’s your secret, and how do you keep the company learning?

— The secret is learning. I’ve always believed that a learning mindset prevents aging. I’ve spread that spirit across the company by trusting and encouraging people to learn and improve every day. I invest in training and create an open environment for fresh ideas. Trust is the bedrock for strong relationships; with it, my team feels confident to innovate and contribute.

Anyone can learn, but the key is daring to trust and act. I’m someone who dares to trust others first—teammates, employees, friends, partners.

In the early days, when dealing with material suppliers and machinery vendors, I openly admitted what we didn’t know and asked for their guidance, while ordering materials to spec. That was how I showed trust. In return, we learned a lot. I wasn’t afraid that revealing my weaknesses would lead to exploitation. When you trust first, people sense your sincerity and are more willing to grow with you.

Likewise, early on, I knew I lacked technical expertise, so I sought a mold engineer to collaborate with. I told our first mold engineer frankly that I wasn’t deeply technical. Once you recognize and confront a limitation, you can choose to trust professionals rather than trying to control everything. By trusting and giving people room to play to their strengths, we made significant technical strides and now master our technologies.

Over decades, I’ve found that the occasional failure from trusting others is insignificant compared to the successes it brings. Of course, trust shouldn’t be blind; it needs clear-eyed judgment.

— As a father, what principles do you teach your children about career and life?

I teach my children to cultivate heart, talent, and virtue. Talent must be paired with heart and virtue. I see heart and virtue as the core of being human; talent is essential, but sometimes applies only to specific fields. My children have far better learning conditions than I did, so their talents surpass mine. With heart and virtue on top of talent, their odds of success rise greatly. This triad—heart, talent, virtue—is a proud Vietnamese tradition and legacy that I strive to follow.

It’s also the greatest legacy I leave my children. Assets can be lost for various reasons, but heart, talent, and virtue endure. With all three, people will love and support you, creating strong networks and opportunities. Ultimately, business and career-building are both journeys of becoming a better person.

— How are you preparing the next generation of leaders at Thien Long?

— Thien Long has had standardized operating processes since the early days. Even in the 1990s, when we were just a small production facility, I wasn’t directly running operations. In 1993, I went to Taiwan to study because we already had a management team at home. Today, professionals run the entire company. With proper processes, I can rest easy—and the company can reach a mature level of excellence. A business isn’t necessarily best when the owner handles everything. Each department at Thien Long is given full authority within its scope. And within our organization, every department prepares a successor—a “seed” for the future.

Thien Long Ranks Among Top 100 Sustainable Enterprises 2025 (CSI)

Thien Long Group has been honored as one of the Top 100 Sustainable Enterprises 2025 at the CSI Program announcement ceremony organized by VCCI and VBCSD-VCCI on December 5th in Hanoi, in recognition of our fundamental and effective efforts in sustainable development.

FlexOffice Highlights Vietnamese Stationery Innovation at Paperworld Middle East 2025

FlexOffice, the export-oriented brand of Thien Long Group, reaffirmed our strong market presence at Paperworld Middle East 2025, the region’s leading international exhibition for stationery and gifting products. The event took place from November 11-13, 2025 at the Dubai World Trade Centre and gathered more than 500 businesses along with many prestigious global brands in the stationery industry.

Thien Long – Vietnamese Brand Writing Sustainability

"The journey of creating simple, familiar products by thien long is the crystallization of vietnamese hands and intelligence, serving vietnamese people and aiming for sustainability" – Ms. Tran Phuong Nga, CEO Of Thien Long Group, shared At Thoi Khac Viet Forum.